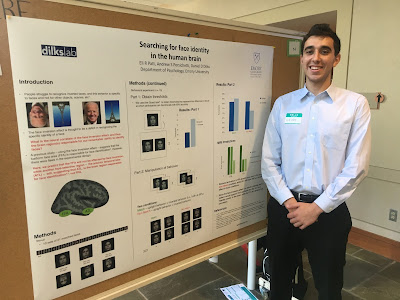

Eli Patt is a senior majoring in Neuroscience and Behavioral Biology. He was awarded a Fall 2017 Independent Grant which he used to conduct research on child development and memory under Dr. Daniel Dilks.

Every Friday at 3PM the Dilks Lab gathers for its weekly meetings. As it nears time to meet, people begin leaving their desks and computers, grabbing tea and snacks on their way to the main conference room. From the coffee machine, one of the graduate students shouts a joke to another, and everyone laughs. The atmosphere is cheerful and everyone is excited to sit around the oval conference table in the main room of the lab.

The meeting begins, and we discuss any business matters first. Usually this is short. Then to the heart of the meeting, most often some form of presentation, talk, poster, etc.

I remember the first lab meeting I attended. It felt like some combination of a well-articulated lecture and a highly contested hockey match. The speaker began, and it was not long before people started interrupting the speaker with questions. Some of these questions related to understanding the presentation, the methods, a past study, for further clarification, etc. Yet others were more pointed and shocked me; people questioned the validity of the methods used, criticized sets of stimuli as the presentation proceeded, and proposed alternative explanations for data that had just been interpreted by the presenter. When the presentation ended, a more philosophical debate emerged. Questions about the underlying theoretical question, the structure and organization of brain processes, evolutionary basses for the mechanisms being researched. At 5PM Dr. Dilks looked at the four undergraduate students and dismissed us, thanking us for attention and participation.

Over the next few months I became more comfortable in the lab, and especially in the meetings. One of the most important parts of becoming comfortable was the encouragement of the other members of the lab. Intermittently during the meetings, the presenter, or another audience member, would stop the lab meeting, checking that I and the other undergrads (and everyone for that matter) understood what was going on. I was encouraged to ask questions, no matter the question, and was especially encouraged to share an opinion when I was most quiet. Before becoming comfortable, there was something that prevented me from asking questions and participating amongst the intimidating professors and graduate students. This “barrier” prevented me from learning from the experience. It was only through becoming comfortable participating, especially with potentially being wrong in participating, that I was able to gain from the experience. This is when I began to learn the value of lab meetings.

Though there are many lessons I learned, I want to share two in particular. The first is the value of the peer-review process, and the second is the value in making mistakes and being wrong.

Take the following example. A member of the lab spends weeks preparing stimuli, writing code, and running ten pilot subjects. They double- and triple-checked everything before starting and were sure that the stimuli most appropriately represented the behavioral paradigm they were attempting to create. They prepare a presentation and are excited to share the data. Yet when ten others are sitting around a table and watching the presentation, someone always finds something to challenge. And it only ever improves the overall project. The questions and criticisms most often lead to productive and constructive change. Alternatively, the presenter may become surer of his work and its validity by standing-up to criticism and having an answer to the questions. Either way, the peer-review process, and moreover, the live, discussion based exploration of one’s work, is critical to ensuring and enhancing the study’s validity.

Furthermore, in these meetings, I have learned the most from the times when I was wrong. Becoming comfortable being wrong is a part of being able to fully participate and learn from the experience. Having the confidence to raise my hand or lead a lab meeting, knowing I will likely be wrong about some aspect of what I am sharing, was crucial to learning the value of lab meeting.

In the end, perhaps the most valuable skill that can be learned from lab is an ability to articulately and persuasively communicate one’s thoughts, ideas, etc. The lab meeting is a place where one is encouraged to speak, and potentially be wrong. By refining my process of thinking and articulating myself, I am working towards that ultimate goal.

Visit the Undergraduate Research Programs website to learn more about applying for Independent Research Grants.

Comments

Post a Comment