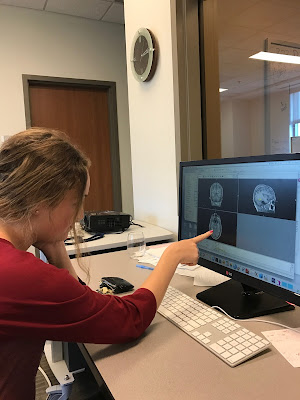

Bethanie Tabachnik is a senior majoring in Quantitative Sciences and minoring in Linguistics. She was awarded a Fall 2016 Independent Grant which she used to conduct research on the brain's ability to identify handwriting and faces under Dr. Daniel Dilks.

Hi! My name is Bethanie Tabachnik and I’m a college junior from Cleveland, OH majoring in Quantitative Sciences on the NBB track and minoring in Linguistics. I’ve been doing research in the Dilks lab since Fall 2015, and my current project is an fMRI study examining how the brain processes identity – specifically handwriting and faces.

We can identify a specific individual (e.g., your mother, your partner, the bully) – usually by his or her face – in a mere glance, distinguishing this person from hundreds of others despite wide variations in facial appearance. How do we accomplish this great feat? To begin to answer this question, considerable research has explored how we perceive faces, a critical source of identity information. For example, many functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) studies on human adults have revealed at least two regions that respond selectively to faces (i.e., responding 2-4 times more strongly to pictures of faces than to pictures of objects or places), including the fusiform face area (FFA) and anterior temporal lobe (ATL). While the face selectivity of these regions is well established, it is not clear whether these regions are simply responding to general face information, or whether they are responding to one’s particular face or identity.

My project aims to identify a region in the brain that represents person identity. We hypothesize that if a region represents person identity, and not just general face information, then it will respond to identity information even in non-face stimuli. For example, while faces may be a primary cue by which we distinguish one person from another, handwriting is another cue with uniquely identifying characteristics that allow a reader to distinguish one writer from another. Thus we predict that if a region represents identity information, then it should respond both when participants are asked to recognize faces and hand writers (since these stimuli contain identity information about people), but not when participants are asked to recognize words or cars (since these stimuli do not contain identity information about people).

The motivation for this research came from an unpublished study, which suggested that the FFA, a face-selective region, would respond equally to face and handwriting stimuli because faces and handwriting have similar characteristics. Past research has lead to the virtually undisputed agreement that the FFA region only responds to faces. Upon reading this study, my PI Dr. Dilks was very surprised with the results, and decided to attempt to replicate the study with no success. As a result, we needed to think abstractly about the results, and targeted our proposed study in a different direction. Reconstructing this study was one of the best learning experiences I have had thus far in my research experience. The process helped me to learn the scientific process in a real world setting through analyzing and solving problems. The initial steps in shaping my project were deciding if 1) the results from the previous study were actually true, and 2) what region of interest our project would focus on and why.

My study predicts that the Anterior Temporal

Lobe (ATL), rather than the FFA, would

have equal activation in response to face discrimination and handwriting

discrimination tasks because it may process person identity. Based on this

prediction, we created an experimental design similar to that of the

unpublished study, and began piloting the task behaviorally. One of the most

challenging aspects of designing my experiment was finding the right tasks to

test the hypothesis. I went through various rounds of piloting after changing

the stimuli or tasks several times. This trial and error experience that I had taught me that all scientific research

takes time and patience, as you won’t get the results you want immediately, and

you might not even get significant results at all. After the many rounds of

behavioral piloting, I was able to start the fMRI component of my study. I went

through fMRI scanner safety training, and then with the help of a graduate

student was able to scan my first participant. Having a research experience using fMRI is not something most

undergraduates have an opportunity to do, which makes my research extra

exciting and worth all the hours put in. For the rest of the semester, I

will be scanning more people to eventually better understand how the brain

processes person identity. Data collection and analysis will be completed by

the end of spring semester, and findings from this project will result in a

poster to be presented at an academic conference, as well as a paper for

publication in a peer-reviewed journal and in the SIRE spring symposium.

Visit the Undergraduate Research Programs website to learn more about applying for Independent Research Grants.

Visit the Undergraduate Research Programs website to learn more about applying for Independent Research Grants.

Comments

Post a Comment