Kasey Cervantes is a Junior majoring in Biology. He was awarded a Summer 2019 Independent Grant which he used to conduct research on Malaria under Dr. Helen Baker.

|

| Figure 1 |

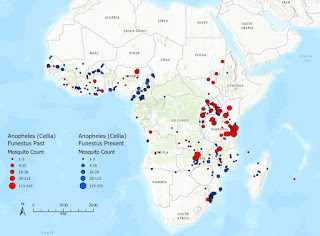

This summer I undertook research into mosquitoes associated with malarial transmission at the Natural History Museum (NHM) in London in collaboration with the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and the Emory School of Nursing (Figure 1). Mosquitoes (Culicidae) are dipterans – True flies, which is one of the orders of insects, the scientific study of which is called entomology.

My journey into entomology started during the second semester of my sophomore year when I contacted a CDC researcher named Dr. Seth Irish, about a summer research opportunity that involved studying the distribution of mosquitoes and their role in malaria transmission. He interviewed me asking about my prior research experience as well as describing what the entomology research entailed. At the end of this interview, Dr. Helen Baker, who works at the Emory School of Nursing, informed me of the Undergraduate Independent Research Grant offered by the Scholarly Inquiry and Research at Emory (SIRE) program that could fund my research trip to the NHM.

I had difficulty at first with writing up the grant application as this was my first time writing up a grant as well as I had no prior knowledge in the field of entomology. To aid me in this process, Dr. Irish provided me with several peer-review journals, helped me outline the research, and provided me with feedback for my drafts of the grant application. Even with his assistance, I had to still read and understand the journals and explain how these journals fit into the type of research that I would be doing, which was the hardest part. Despite the writing of the grant being challenging, I submitted the grant, received funding from the SIRE program and headed out to the NHM in London in August.

|

| Figure 2 |

The mosquitoes dated back to the early 1900s and despite all my care, I broke a lot of legs and wings of mosquitoes, as a lot of the specimens are fragile. One small pinch or bumping into the pin, can cause ligaments to break or fall. Dr. McAlister came back from a conference, that first week, and I was worried that she may have a heart attack after seeing that some of the mosquitoes were missing legs. She did but didn’t hurt me, instead she taught me a better method on how to reduce damaging of the specimens by working one at a time. In having Dr. McAlister point out what I was doing wrong and what to do to recover damaged ligaments of the specimen, my specimen manipulation skills greatly improved. Over time I started to work a lot faster, so I went from cataloguing 100 mosquitoes a day to around 250-300 mosquitoes by my last week.

|

| Figure 4 |

These distribution maps and data of malaria vector mosquitoes can help improve the accuracy of present-day distribution maps. A big problem in addressing the prevention of malaria in Sub-Sahara Africa is monitoring the mosquito biodiversity, specifically determining the malaria vector mosquitos and non-vector species. In order to reduce malaria risk, malaria vector mosquito’s information must be collected and mapped to determine the transmission and control efforts of malaria throughout the continent. With this information I databased, models can be created to help determine where malarial control programs could be necessary.

This experience introduced me to the world of entomology, something I didn’t even know existed before this project. Every day, I enjoyed working hands-on with the diptera collection in the NHM because of how important this type of research is for entomologists to assist in the fight against malaria. Working on this project was amazing because I was able to have a part in helping this issue. Finally, I think if someone is given the chance to study abroad at least once in their time here at Emory University, they should take full advantage of it. Emory University also did an article on this research project.

Visit the Undergraduate Research Programs website to learn more about applying for Independent Research Grants.

Comments

Post a Comment